How to Finance a Large-scale Solar Thermal Plant

One of the organisations which have had experiences with RES leases over many years is the Austrian UniCredit Leasing. Josef Robert Straninger, Country Coordinator of the Competence Center Renewable Energies at UniCredit Leasing, explained at the SMEThermal conference in Berlin what steps are necessary to ensure the successful financing of large-scale projects (see the attached presentation). After the conference, solarthermalworld.org asked the expert about what he thought needed to be done and what he believed was important when financing a large-scale solar thermal plant in particular.

One of the organisations which have had experiences with RES leases over many years is the Austrian UniCredit Leasing. Josef Robert Straninger, Country Coordinator of the Competence Center Renewable Energies at UniCredit Leasing, explained at the SMEThermal conference in Berlin what steps are necessary to ensure the successful financing of large-scale projects (see the attached presentation). After the conference, solarthermalworld.org asked the expert about what he thought needed to be done and what he believed was important when financing a large-scale solar thermal plant in particular.

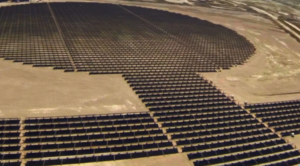

Photo: Stephanie Banse

solarthermalworld.org: In 2011, UniCredit Leasing’s RES project volumes amounted to EUR 1.724 million. Projects came from the sectors of wind, PV, hydropower, geothermal, biomass and biogas, but there was no solar thermal plant among them. Why was that?

Josef Robert Straninger: It’s quite simple: The business model for cash flow financing which I showed in my presentation depends on feed-in tariffs guaranteed by the state. The situation does get more complicated if – instead of a tariff – you deal in green certificates, which have to be re-sold on the market, for example, in Romania. We now have models for this, too. But when you first have to sell the generated energy to big customers, it often happens that the calculation resembles more a game of chance and the risks seem too great. Also, a forecast about a financing period of 10, maybe even 15, years will undoubtedly involve a lot of speculation about future events. This is why we haven’t shown any interest in solar thermal until now.

solarthermalworld.org: And in the future?

Straninger: Overall, the amount guaranteed by feed-in tariffs is getting lower and lower while electricity prices keep on rising. So, we have already tried to calculate the first PV projects based entirely on power purchase agreements (PPA), namely in Southern Italy. If this works, chances are that we can also apply the concept to solar thermal and heat sales to big customers. In addition, our biomass and biogas segments have already shown characteristics similar to solar thermal. These segments do not offer any state-guaranteed feed-in tariffs for additional heat either, but purchase agreements with big customers. Solar thermal is a completely new thing for us. We have not touched on the topic yet and do not know the technology. But we have said before that if someone showed us a project in this area, we would have a closer look.

solarthermalworld.org: In our opinion, does solar thermal technology present you with any additional challenges or special requirements?

Straninger: Talking to a big solar thermal company has made us realise that our 2 million minimum project volume for cash flow financing sets the bar too high. Some banks even start with no less than EUR 5 to 6 million. This means that we not only have to adjust our model to the technology, but also to a lower project volume. Especially the risk assessment prior to the project’s start creates considerable costs, which no project below EUR 2 million has so far been able to cover. But it does not mean that there isn’t a way to make the process less expensive. For example, the Italian PV projects benefit from the fact that we have already installed several systems in the region and can now reduce assessment costs because of our experiences with these previous projects.

solarthermalworld.org: How long do you think it would take to finance a solar thermal project?

Straninger: Well, financing a PV or wind project usually takes 10 years or more. Our model allows us to finance projects up to 17 years. Nowadays, the average financing period is between 10 and 15 years, depending on how long a state guarantees the feed-in tariff. To your question about solar thermal: We don‘t have a clue since we haven’t done it before and cannot base our assessment on tariff run times. It will depend on both the run time of the PPA and the revenue which can be made, including the related IRR (internal rate of return).

solarthermalworld.org: Could you please sketch the cash flow financing of a large-scale solar thermal plant?

Straninger: Usually, we will only look at a project if project development is complete. We need to make certain that the project can really be done, that all permits are in order, etc.

The first thing we need is a project teaser. In addition to the teaser, we may draw up a questionnaire if necessary. The customer can fill in this questionnaire to let us gain an overview of the entire project. What is the aim of the project? How will you achieve revenue? What technology do you use? And: how far is the project? The answers to these questions will help us decide quickly if the project is interesting enough to warrant further attention.

In a next step, we will work out the so-called structure in cooperation with the customer. Together, we will develop the possible financing of the project. This includes specifying all variables, such as run time, payback rate, securities, etc. We will eventually arrive at a non-binding quote. Customers signing this quote will not enter into any binding agreement. But confirming the quote will be taken as a sign that they are still interested in the cooperation.

Then, the real work begins: We need to assess the project up to the last detail and adjust its parameters until our risk management can approve it. This department is responsible for evaluating a project according to the existing rules on risk reduction and financing possibilities. When the people in risk management give their OK, it means we are prepared to finance the project.

After the approval, it will be time to create and sign the leasing contract. This also involves checking all the conditions and securities included in the contract and, for example, filling in the relevant data during land registry. If all requirements have been met, we will pay out the money according to the agreed-upon payment plan.

solarthermalworld.org: How long is this initial stage?

Straninger: Our experiences show that it will take at least 6 to 8 weeks, sometimes even several months, until everything is ready. It all depends on how good the investors prepared the project and how many parameters influence energy generation. For example, generating energy with biogas is a more complex process than with PV or solar thermal. Another factor is the size of the plant: smaller ones usually take less time. I would place the start-up time for solar thermal plants more at the lower end of the spectrum – at least, after we will have financed the first plants and have had our first experiences with the entire process.

solarthermalworld.org: In your presentation, you were talking about project killers. What could a project killer look like in the solar thermal sector?

Straninger: All factors that I listed in my presentation – for example, incomplete information about the project, not yet finalised project development or a bad record of accomplishment of the project developer, investor or technical partner – can also be project killers for a solar thermal plant. Another factor especially in case of solar thermal systems is the heat purchaser. For example, it could kill a project if there is no guarantee that the energy user will remain creditworthy throughout the entire financing period. This factor, however, will also be affecting other technologies the more we move away from feed-in tariffs.

solarthermalworld.org: In your presentations, you mentioned a stress test for cash flow financing. Could you please describe how this test may look like for a solar thermal plant?

Straninger: The crucial question in financing a project is always the same: How much revenue will the project create compared to how much it costs – meaning, which cash flow will the project be able to attract and will it be enough to pay back debts? The Debt Service Cover Ratio (DSCR) must be greater than 1, meaning the project has to bring in more money than has to be paid back.

First, we look at the customer’s realistic business model and calculate whether it adds up. Then, we think about factors which could worsen a customer’s income situation. Which factors the stress test will include depends on the technology, as well as the relevant market. In case of a thermal plant, I could think of calculating a year with extremely low radiation, as this is precisely the factor which varies from year to year. On the other hand, we could calculate the influence of increasing interest or exorbitant maintenance costs because of increased wear and tear of mechanical parts. This means that the stress test offers theoretical possibilities, which nevertheless could occur. And if the worst case is there, the DSCR should still be at least 1.

solarthermalworld.org: The DSCR of plants you have financed ranges between 1.2 (wind, PV) and 1.4 (geothermal). Which criteria determine the DSCR and which DSCR would you estimate for solar thermal plants?

Straninger: The greater the seasonal effect in cash flow and the greater the variations expected over the years, the higher we set the DSCR. Personally, I’d place solar thermal in the middle at 1.3.

solarthermalworld.org: Which RES sector is in the focus of UniCredit Leasing at the moment?

Straninger: There is no intended focus. We offer it all, but we provide what the market demands. We made our largest investments in the wind sector, but we have the biggest number of projects in the PV area.

solarthermalworld.org: The more secure and established the government promotion is, the higher also your number of project in this area?

Straninger: Yes, that is correct. An example: At first, we had only financed wind projects in Germany. Later, we began to add PV installations. Of course, we will not go against the market. But we offset risks by financing different technologies. Different technologies with different requirements mean balancing the risk in our investment portfolio.

About UniCredit Leasing:

With more than 3,000 employees in 19 countries, UniCredit Leasing is one of the leading companies in Europe for asset-based financing solutions. It is part of the UniCredit Group, one of the major financial institutions in the world. Headquartered in Milan, Italy, UniCredit Leasing has subsidiaries in Austria, Germany and Italy and in the emerging markets of Central and Eastern Europe: Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Russia, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Turkey and the Ukraine.

More information:

http://www.unicreditleasing.eu